The Renovation: A Historical Perspective

By Ammar Khammash.

Artist and architect who restored the first three houses of Darat al Funun.

During the first decade of the 20th century Amman was a small town with a population of hardly 2000. The advent of the Hijaz Railway in 1903, with its large station in Amman, and numerous impressive bridges within the immediate vicinity, led to a whole series of changes which transformed this sleepy town in ways previously unimaginable. Never had Amman witnessed such an awakening of construction activity since Roman times, two millennia ago. It was a new beginning for the modern city of Amman, with roots going deep into the past, for Paleolithic remains show that the water springs of Amman have made the site attractive for human habitation for more than 12,000 years.

Darat al Funun in the 1930s overlooking downtown Amman

Spurts of construction during the Byzantine and Islamic periods came to a complete halt by the end of the Mamluk era, about 500 years ago. Amman’s construction history during the period which started immediately after the golden days of Roman Philadelphia and continued right down to the end of the Ottoman rule at the beginning of the 20th century, could be generally characterized as one of constant decline. While the Philadelphians of the 1st century BC had to toil in virgin quarries to gather construction stones from the hillsides, many of which are still preserved, builders of the Byzantine and Islamic periods used stones from Roman structures for their buildings. This recycling of building blocks became a tradition that lasted until few decades ago. Stones from the streets of Roman Philadelphia can be found today in downtown Amman in the courses of side-elevations in buildings of the 1940s.

While the people of this city in Roman times cut their building blocks anew, imported pillars of granite from Luxor and marble capitals from Rome, they provided building stones for generation in the Byzantine and Islamic periods. With the occasional help of a few powerful earthquakes, each new generation of builders used earlier structures as quarries with stones detached and shaped in a way that made it easy to use or cut them into smaller sizes and new shapes.

The first group of Circassians arrived in Amman in 1878. A few families settled in existing ruins such as the vaulted rooms and passageways of the Roman theatre, parts of the Nymphaeum, and other ruined structures and caves on the eastern side of the citadel hill. What is now the downtown commercial area, stretching from the Roman theatre to Ras al Ain, became a green valley with cultivated fields of vegetables and fruits irrigated by the small creek that came from a spring at Ras al Ain, now under the new Building of the Amman Municipality.

The Circassian tradition of skilled woodwork, clearly better than that of the local semi-nomadic Arabs of the region, was visible in the way they built their houses, with the extensive use of cut timber as a structural element with ornamented edges, typically seen in the detailing of porches at the front of their houses.

Circassian master-carpenters also surprised the local Arabs with their production of transportation carts. A trademaker of Circassian skills in wood and a symbol of identity, these carts were quite complex. Their elaborate enlongated baskets were made of branches woven on a frame of oak. The wheels were of wood, each protected with a ring of iron. These carts were pulled by oxen or horses, and were laden to the top with crops at harvest time. Once again, the landscape of Amman was trodden by wheeled carts as in Roman days, and wheels came back into daily life after being forgotten for almost 2000 years.

Location of Darat al Funun

The main house of Darat al Funun occupies a strategic location at the Eastern tip of what is now called Jabal Weibdeh. Fragments of Roman pottery and architecture, the remains of the Byzantine church with caves and cisterns, and other vestiges of different Islamic periods tell us that this very location was chosen by many in the past as a desirable site for building.

Just 60 meters above the two dry valleys that slope towards the East, one leading to Wadi Saqra and the other to Abdali, and commanding their meeting point below, the site of Darat al Funun displays some geomorphological qualities similar to those of the Amman Citadel. Both sites are attached to bigger hills to the West, surrounded by valleys in other directions. The main difference between the site of the Citadel and Jabal Weibdeh, besides the latter being higher and larger, is the smaller connection of the citadel site to Jabal al Hussein. This neck, being less than 50 meters wide, made the site almost fully detached, and thus easier to protect by complementing natural defenses with a fortification wall a solution that Ammonites of the 7th century BC as well as the Philadelphians put to use.

The traditional floral and geometric designs of the tiles at Darat al Funun.

As both the Citadel site and that of the Darat al Funun overlook the valley below, the site of the Darat al Funun has a commanding view of a segment of the tributary valley that meets the main valley of Amman, through which a small creek used to pass. At the T-junction still stands the Nymphaeum. In Roman times, a colonnaded street was built, passing in front of the theatre. A barrel vault, allowing the creek to pass below, might have supported parts of the street and created a flatter site for the Roman downtown area.

From the vicinity of the Nymphaeum, from the site of the Hussein Central Mosque, ran another street northwest. Part of this street was exposed by chance when the eastern side of the Haifa Hotel, an early 20th – century building just to the east of Arab Bank building, was demolished in 1997. In a northeasterly direction, this street had no choice but to split into a fork, at a point from which connecting steps could have led to the site of the Darat al Funun. Today, two millennia later, the situation is not very different.

When the main house of the Darat al Funun complex was built, around 1918, the surroundings had a different atmosphere from what we see today. Then, by the end of the second decade of the 20th century, the small market of Amman started to grow very rapidly, reaching a scale that exerted outward pressure, pushing the new residential construction sites uphill in all directions, to the sloping hillside of Jabal Jofeh, the Citadel. Jabal Weibdeh and Jabal Amman.

These new neighborhoods became fashionable with a construction boom, as is manifested in houses of a status different from those built by the Circassian settlers or the Fellahi houses built by some of the Balqa clans. Unlike that of the rural, peasant houses of the early settlers, the construction boom of Amman of the 20s was characterized by houses of unconventional sophistication, palatial, and in the tradition of the latest style then prevailing in cities east of the Mediterranean. Of the three Darat al Funun houses, the first and the third demonstrate most clearly the prototype then in fashion in cities like Beirut, Haifa, and Jafa. Strongly influenced by Venetian style, the examples found in Amman of the 1920s represent an extension of this Mediterranean architecture to the furthermost point towards the east, the brink of the Arabian desert. In Jabal Weibdeh alone, at least 30 houses were built of this period-style, most of which can still be found among the accumulating housing stock of later periods.

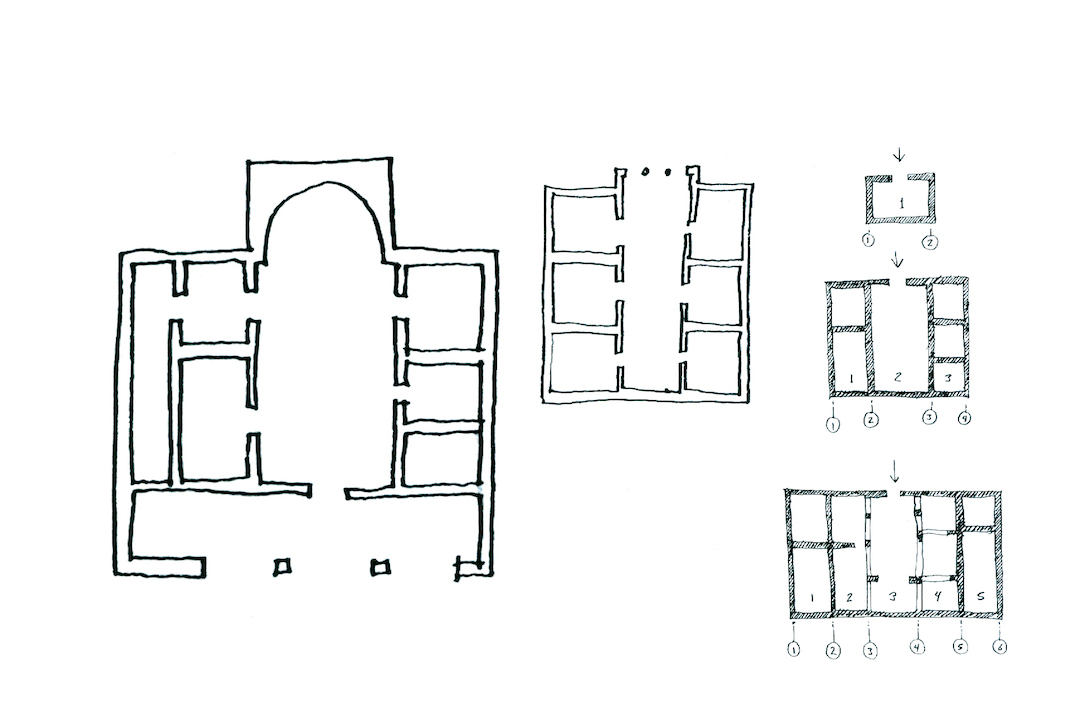

The houses of the Darat al Funun type have a symmetrical floor plan, a central hall with a line of rooms at each side. The central hall often has a porch with pillars covering the front entrance; while at the other end of this hall is another back entrance. Both of the two entrances of this central hall are located in the middle of each end wall, having rooms on each side. This central room can only receive sufficient light from windows symmetrically flanking each door in the front and back walls. Being oblong, with a length at least twice its width, the central hall becomes the connecting space for the rooms on each side.

The side rooms are almost square, with doors leading from each room to the other, directly beside the door that leads to the central hall. In such a layout doors are numerous. Up to 8 doors can be found in the walls of the central hall, and 3 in the walls of the side rooms. These houses had floor plans with doors in abundance, but in terms of the privacy of the individual as we see it today; they left much to be desired. From the front porch, doors leading to the side room are used by guests to enter without passing through the central hall, thus providing privacy only to protect the members of the household from outsiders, rather that one member of the family from the other.

Typical floorpans of 1920s three-bay houses.

This typical floor plan of the 1920s, referred to as “the central hall house” or “the three bay house,” could be seen as rooms surrounding a small roofed courtyard. Its origin is also explained by looking at the structural logic of symmetrically combining negative spaced with walls in between.

Similar to typical floor plans of barns, churches, and many other prototypical structures, the central hall house has three lines of roofed spaces contained by four lines of structural walls. This arrangement of an odd number of voids and an even number of structural lines also works on different scales, the only difference being that one void and two side walls provide a single room or a linear house one-room-wide, whereas five voids and six structural lines, or any bigger odd number of void with bigger even numbers of structural lines, would result in a dark room at the centre of the building.

Cases of ancient churches with five voids are rare, the only one in Jordan being from an excavation at Um Qais in 1998. Looking at the floor plan of the main house of Darat al Funun, one can see a great similarity to that of a typical Byzantine church. With a similar West-East orientation and a semi-circular eastern elevation, it is important to realise how the site, with its Byzantine church, might have influenced the design of the house.

Partially cut into the natural bedrock, the northern elevation of the church must have given the house its orientation, and a drop in the rock on which the house sits made it necessary to raise its eastern half on a basement. In this basement one can see parts of an ancient cistern and a mosaic floor.

The way in which the two oldest houses of Darat al Funun – the first and the third – were built demonstrates a structural system in transition.

Walls were built with two layers of limestone with mud mortar in between. The outer layer is of hewn blocks of stone placed in clear courses, while the inner layer is of rubble stone of smaller sizes and with informal coursing. These outer walls range from 40 to 60 cm in thickness and could thus be depended upon to support another floor or just the roof above.

Unlike the structural system used in houses today, a post and beam frame of cast-in-place reinforced concrete, the structures of the 20s were built as boxes of walls that share the load of the roof.

When the houses of Darat al Funun were built, concrete had been known to local masons for only a couple of years. They used it with caution, where the traditional materials presented obstacles – in roofing big spans or under tension. The perception that this new material had unconventional abilities to fulfil old duties was hindered by the dubious attitude of local builders and by the cost, for cement was imported from across the Mediterranean Sea. One decade before the arrival of cement as a manufactured building material, steel was introduced to Jordan through the Hijaz Railway, and finally this part of the world received the first samples of concrete products of the Industrial Revolution of the West.

The outer walls of the main house were built in a tradition that goes back at least 10,000 years. The two layers of stone with mud mortar represent a solution dictated to local builders by the local ecology for thousands of years. In Darat al Funun, the use of dressed stones in the outer layer is reminiscent of the way in which Roman walls were built.

Even the way in which stones were cut to fit within courses, rustico, with bulging random belly, surrounded by a finely hewn frame and sharp corners, represents a direct continuation of the Roman style, reintroduced by the Italian stone masonry brought in for the structures of the Hijaz Railway.

Detail of the capital of the Main Building front porch.

Also descended from Roman capitals are those on the pillars of the front porch, decorated in simple foliage motifs. In the Roman tradition, the Acanthus leaves were given a full third-dimension, with parts partially detached from the bulk of the stone and suspended with fragile connections; these leaves are part of a comprehensive overall composition that gave the capital its visual impact. As is often the case with traditions, similar foliage was repeated from one era to the other, and with very reproduction, from the Byzantine into Islamic times, the capital lost part of its original essence.

The capitals of the main house of Darat al Funun are the end-product of a long typology line – they are peculiarly eclectic, with fragments of visual elements reminiscent of classical Corinthian, flatter Byzantine foliage with a straw basket motif, and the Islamic tradition of plaster relief work as in the Umayyad Palace at the Citadel. It is important to note that this mix of decorative styles was not intentional, since stone chisellers were not art historians. It is just the product of the style that was in fashion, based on an accumulating aesthetics with a long chronology. Also while examples of the past were accumulating, the quality of craftsmanship was diminishing. To avoid the accusation that this is an “Orientalist view” of the course of history, one should stress that we are here referring to a regional case on a very small scale, as the story of architectural influences greatly differs when looking at Cairo, Aleppo, or Damascus.

From the kind of stone, soft yellow limestone, we can tell that these pillars, and many of the other worked stones of window and doorframes, were brought in from the town of Salt. Whether the stone was carried on camels from a distance of some 40 km, from quarries above Wadi al Middan west of Salt’s historical centre, and whether uncut or in a finished state, is uncertain. At least in the case of the four pillars of the front porch, it would have been more practical to transport them cut.

In the courses of the outer walls one can find stones from different sources. All of them are limestone, but some are whiter or harder than others. Occasionally, some of the stones are of a conglomerate rock, with darker shades and visible pebbles of harder stone pressed together. Within this collection of geological samples, archaeological fragments are also used. In the lowest course of the Southern elevation of the main Darat al Funun house is a stone with a relief of a Byzantine cross. Placed carelessly, this building block, recycled from the remains of the church, shows that the builders of the Darat al Funun were dealing with it as a mere building unit and not as having any ornamental value. It is very possible that these walls contain other archaeological stones, with their decorated or inscribed sides facing inward – a possibility to be left for future scanning breakthroughs or for our creative imagination.

It can be said that the three houses of the Darat al Funun style, built in Amman in the 1920s, represent a continuation of the architectural boom of the town of Salt after its climax, when it was already in decline.

These houses can be seen as the last examples of influences from cities of the Levant, before the arrival of international trends, with an even stronger shaping given by the influence of new industrialised building materials, already seen in structures of the late 1930s. With the breakaway from regional skills of construction, where structures were the product of local crafts, and with the introduction of Western engineering, with specifications determined by the market of industrialised materials, architecture was the loser.

Unable to remain architecturally self-sufficient, society slipped into the global trends of house building. As architecture has move closer to being produced in factories, it loses its role as a social institution, which used to provide maximum job opportunities, training in traditional skills, and hallmarks of regional identity.

The Renovation

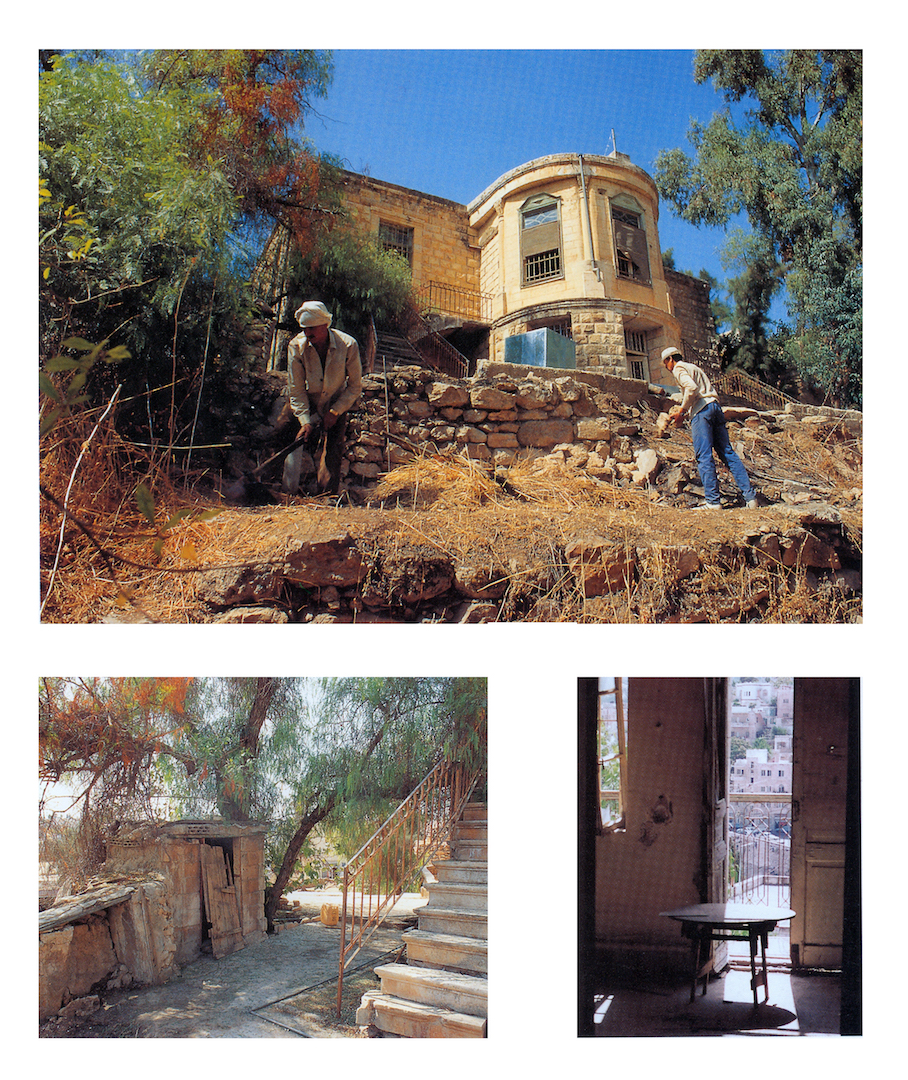

When renovation works started in 1992, the first house was in a critical condition. The main floor had by then been deserted for 15 years, and the last occupant of the basement, an elderly woman had passed away. Only in the small shop on the street that passes East of Darat al Funun was a modest workshop of carpentry; the rest, the house and the garden with its archaeological remains, were dormant under a layer of decaying eucalyptus leaves.

The renovation of the Main Building.

Renovation, or adaptive re-use, was based on principles that were kept in mind throughout the intervention phase and are still, nowadays, of great importance in the management and presentation of Darat al Funun.

With minimum intervention, changes were limited to those, which help synchronise the new function of the buildings with heir inherent qualities. A lack of proper renovation know-how is subjecting most of Amman’s architectural heritage to harsh treatment such as severe scrubbing, sandblasting, and painting of stone facade. Such acts of compulsive whitening are responsible for the effacing of a vital feature of stone workmanship – chisel marks. This insensitive treatment is not only responsible for erasing forever traces of traditional stone tools; it also inflicts irreversible damage since the crust of the stone is set on a course of perpetual decay.

The stone elevations of the houses of the Darat al Funun were left untouched. They retain the fragile marks of tools that were once held in hands of strength and skill. In these elevations resides a hand-written text; the footprints of chisels that once rang under the impact of the hammer; and the identity of an individual stonemason.

Architecture can be seen as a record of past decisions. New decisions can be added, provided that they do not erase, distort or overpower previous ones. New intervention at Darat al Funun was kept visible and with maximum reversibility.

When the new addition of the library was conceived, a special structural system was chosen. The addition was built out of concrete blocks to make a clear contrast with the old parts, avoiding the use of stone, which might have created an unpleasant mimicry. Contrast between the outer walls of the old building and the library addition above was limited to the texture of walls, without a great difference in colour, to give the sunlit elevations the chance to play with the shadows. A thin tint of soil, taken from the Darat al Funun garden, was applied, in order to tone down the new plaster.

To avoid the concentration of loads at corners, the new addition was built without the use of columns. The load-bearing walls, built of semi-hollow concrete blocks, kept the addition light, evenly distributing weight on the old walls below, and reversible, so that should the library be dismantled, no heavy machinery would be needed.

The fact that the Abdul Hameed Shoman Foundation has chosen to renovate three of the old houses of Amman to become Darat al Funun gives a clear message, celebrating Amman’s architectural heritage and resisting fashionable expansions. The traditional character of Jabal Weibdeh has been enhanced, in a way that gives the community and the very neighbourhood a renewed sense of cultural value.

From the publication Darat al Funun: Art, Architecture, Archaeology, 1997.